I’ve been trying to write, but my asthma is troublesome, between spring pollen and wildfire smoke. I wrote this for my father, and he has given permission to publish it.

“A good man leaves an inheritance to his children’s children.” - Solomon’s proverbs [12:22]1

My father’s roses are in bud. He brought them from his family home in Nova Scotia. A heritage variety, they are hardy, but have struggled in recent years. As my siblings and I grew up and left home, the flower gardens we helped tend fell into weeds. A misplaced patch of lily-of-the-valley started strangling the rose roots, paving the way for pestilence and disease. I brought the roses back from the brink a decade ago. These last couple of years, I’ve been combating a resurgence of their old enemies.2

My mother tended our gardens when I was a child. My siblings and I helped, as part of our chores, with planting, weeding, eliminating pests, and harvesting. My father lent a hand, but he worked long hours, had wood to cut, and maintained the house and vehicle. My mother, who was the strongest woman I know, became progressively disabled with rheumatoid arthritis, and when my last sibling married, it seemed there could no longer be a large vegetable garden. But my father, now retired, stepped in. The year he took over, I was home, recuperating from serious illness. His garden was a thing of unexpected beauty and abundance.

I am not a natural gardener. Neither is my father. His father was a subsistence farmer, still using horses in the 1950s, but the family farm was sold when my father was still a boy. It is my mother’s side of the family who are generally gifted with the instinctive ‘green thumb’. My father learned to garden just as he learned so many other life skills, out of necessity. After he debuted his vegetable garden, I set out to save his roses.

We think alike, my father and I.

Mr. Fix-it

My father instinctively solves problems. It was his profession, after all. From the late 1960s to the late 2000s, my father repaired office equipment. Originally trained on mechanical cash registers, he adapted as typewriters transitioned from mechanical to electric; as manually programmed adding machines were replaced by automatic calculators; as printers, copiers, and fax machines went from analog to digital. He also adapted when his local employers sold out to a national company with efficiency quotas that did not fit the sprawling rural area my father served. He might drive hours between calls, so he sometimes improvised repairs, with paper clips and old credit cards, until replacement parts were delivered.

My father’s ability to improvise kept us out of poverty. Office equipment service technician was not a high-paying job and he needed a car in order to work. My father didn’t just change oil, tires, and brake pads; he taught himself to replace timing belts, transmissions, and engine gaskets, improvising the tools that were too expensive to buy. He once built a compressor, for wheel strut springs, out of a tree stump and a cedar log. He also brought home defunct office equipment, to repair and use, before most people had personal printers and scanners.

In addition to fixing things, he created them. In the 1970s, land was still cheap, so my parents bought an empty lot. My father drew the house plans himself. Both my parents worked alongside the neighbourhood contractors hired for each building stage. Then, my father proceeded to maintain the house – wiring, plumbing, renovation, etc. – himself. He spent one of his yearly holidays replacing the shingles with metal roofing, singlehandedly. When he read us The Little House on the Prairie series, I thought Pa must have been like my father.

I learned to hammer nails, put in screws, drill, saw, and fill and paint a wall from watching my father. As a child, I took mechanical and electric analog equipment apart out of curiosity. It didn’t occur to me that in becoming a nurse, I was following my father’s tradition of repair. But after earning my degree, my first job was in the same town where my father’s central office had been. As he helped me find a reliable car for community nursing, I remarked the only difference between us was that I repaired humans, while he had repaired machines.

My father still helps maintain my car. He also assisted when I renovated my little living space. I planned it, purchased the materials, and worked alongside him, but my uncertain health and small size mean I cannot do everything myself. Together, we developed the rotating bookshelf that holds most of my library. In my childhood, he made me a dollhouse. I solved the problem of how to keep the miniature house in my limited space, creating furniture to accomodate it.

Walking Encyclopedia

My father’s highest official level of education is high school diploma, but he has never stopped learning. He built bookshelves throughout our home and filled them. His classic fiction, encyclopedias, over two decades of National Geographic magazines and multiple other periodicals, biographies, histories, atlases, books on exploration, car and home repair manuals, and more, shared the space with my mother’s books on gardening, crafts, natural remedies, teaching material, and vintage school readers. Before the internet, we already had a world of knowledge for our perusal.

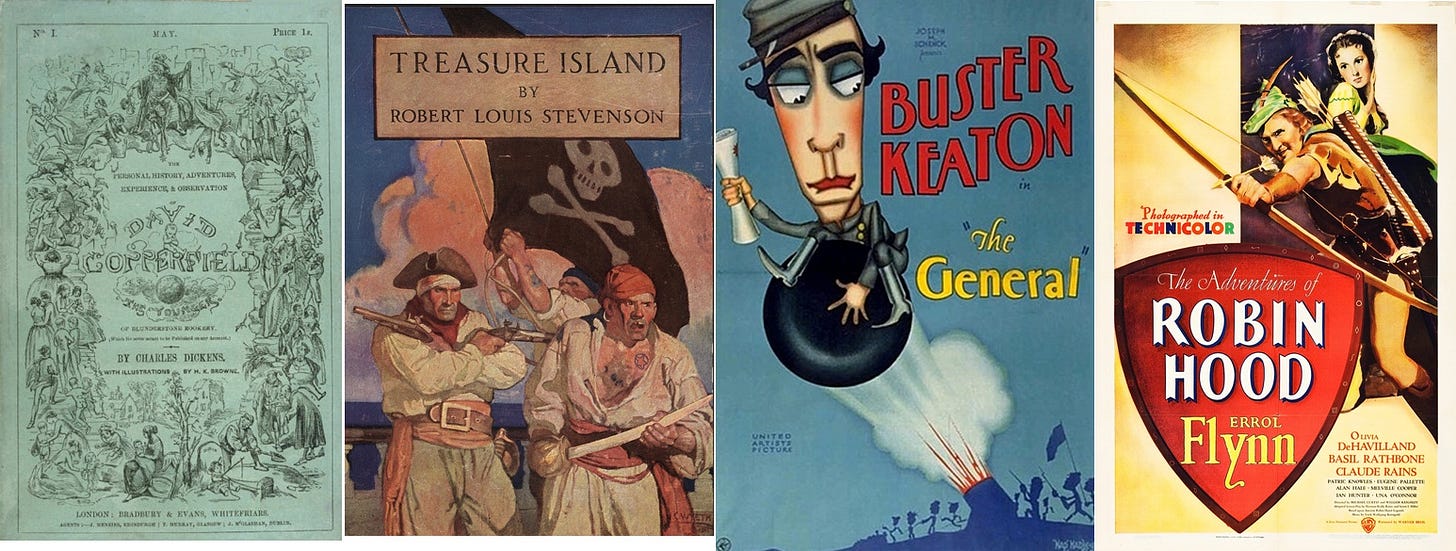

In Love the World, I told how my father gave impromptu geography lessons at our supper table. After supper, he often read classic fiction to us as we washed the dishes. He ran reel-to-reel films for us and gave videocassettes of classics at birthdays. He had eclectic records – Gordon Lightfoot, Tijuana Brass, The Moody Blues, etc. – from his bachelor years, which he often sang in quotation.3 By the ‘80s and ‘90s, he was recording mix tapes of classical music, staying up late to record performances of symphonies and other works. Whenever we missed the announcer on the classical radio station, my father could usually name, not only the piece and the composer, but also the orchestra and conductor. Despite his ear for music, he never learnt an instrument. Instead, he paid for us to have music lessons.

I inherited my father’s photographic memory, although my synesthesia is different than his.4 He has a three-dimensional timeline in his mind – spatial-sequence synesthesia.5 I read not only my father’s classic novels – he and I share a love of Dickens – but also the encyclopedias and National Geographic magazines. I listened through his mixtapes, although I could never recognize orchestras the way he did. In adolescence, my family started giving me the same moniker as my father, ‘walking encyclopedia’.

Itchy Feet

My father has an endless curiosity to see the world, inherited from his mother. During her long widowhood, she not only travelled herself, but also followed her family’s journeys in her atlas. It kept her connected to her children scattered across Canada. We often heard stories of my father’s car trips. One story he retells is the time he flipped his VW Beetle on an icy road in Vermont. After a tow truck flipped it back, my father popped the roof out again, but the oil had drained out of the engine and the drive belt had slipped. Using heavy oil from the tow truck driver, he made it to his relatives in Boston, so he could get the car repaired before going home for Christmas.

On road trips, my father drove as long as possible, only looking for a place to sleep after dark. In another of his bachelor stories, he couldn’t find an empty room in western Ontario, until a hospitable police officer provided a bed, in an empty cell at the local station.6 My parents remember camping after dark in the Rockies and waking up next morning to the chill of a glacier just metres away. But the worst was the time we tried to set up camp after dark in Maine, and were driven away by the mosquitoes. We learned from infancy to endure long car rides, frequently made longer when my father went out of his way to see a landmark, or took a different route back home, navigating by one of his many paper maps.7

The first journey I took outside of Canada and the U.S. was with my father. We joined a team building a community centre in northern Mexico. My father loved it. Despite knowing only a few words and phrases in Spanish, he worked with a local builder, who, like himself, improvised tools from limited resources. We stayed in a walled and gated house with window bars, and were told to keep together for safety; but my father sometimes went off alone. The only day we went touring, I saw the horror in our guide’s face when he noticed my father was missing. He had gone to photograph a landmark.

My father’s insouciance was exasperating, but in retrospect, I am like him. My first solo journey was to help someone I encountered in an internet comment section.8 My extended family thought I was naïvely trusting, even my father was worried. But I returned safe and sound, and my father later went to help the same family. That first journey started a sequence of events that led me across the ocean. Wherever I’ve gone alone, I’ve always known what to bring back for my father – a paper map of where I’ve been. I have his sense of direction.

These days, my father travels Google Earth. He has followed street view through entire cities and along transcontinental highways and railways. He deciphered the Cyrillic alphabet just from reading street signs. Sometimes, one of his grandchildren will join his virtual journeys, the family inheritance of ‘itchy feet’ being passed on to the fourth generation.

Nine Lives

My father has always been a risk taker. He tells hair raising tales of his boyhood, exploring a forest full of sinkholes, encountering lamprey eels while swimming, building a hydrofoil with his friends and testing it on the local river. In his bachelor days, he souped-up his Datsun for drag racing, on and off road – he once spent a night with his car embedded in the sand by Lake Ontario. When he started dating my mother, she had to sit on the floor of his car, because he had removed the passenger seats to make the racing modifications.

Sometimes, his risk taking is unintentional. Problem solving is his strength, and greatest source of danger, as he focuses so intently on a task that he forgets his surroundings. The teacher at my father’s two-room school told his mother that she could speak to him when he was concentrating, and he wouldn’t hear her. It is a trait I share – whenever I am reading, my family have a hard time getting my attention.

My father has, over the years, gotten deep cuts and puncture wounds, split his scalp, lost the tips of two fingers, amputated a toe, and, most recently, dislocated an arm, all due to concentrating on a problem more than the surrounding danger. He has also miraculously avoided injury, like the time the barn frame he was demolishing started collapsing one way and he exited in the opposite direction.

I’ve practiced my wound care skills on my father more than once. Yet despite needing stiches, getting infections, tearing ligaments, and even surviving pulmonary embolism, twice, he always bounces back.

His most serious injury was not his fault. Nearly thirty years ago, my father was driving to a repair call along an icy highway. He remembers a line of traffic approaching and a car skidding towards him. The rest of the memory is lost. He was conscious when he was extracted from his car, but the local hospital couldn’t set his compound fracture until a surgeon came. When my mother phoned the hospital the next morning, my father was in a coma. Fat from the marrow of his broken femur had entered his blood, blocking circulation in his brain and lungs.

He was placed on life support and airlifted to a large city hospital. My mother slept on chairs in the ICU waiting room, not knowing if he would ever wake up or recognize her again. He woke up slowly, only gradually remembering. My mother now laughs when she remembers testing his memory, asking how long they had been married. He replied, after a pause, “A hundred and twenty years.”

He fully recovered. Cognitive tests confirmed what we had always known about him, that he could do anything he wanted, even become a brain surgeon. But he was left with blind spots in his vision. When he tried reading aloud, his once confident voice was hesitant, as the blank spots slowed his ability to scan the words.9 Since his condition was so rare, multiple specialists examined him to discover whether his vision loss was due to brain or eye damage, but no conclusion was ever reached. He stopped reading to us.

In the last few years, he has started reading more. He says he no longer notices the blind spots. As he nears completion of his eighth decade, he is slowing down a bit. He can no longer carry around whole tree trunks these days, he has to cut them into quarters or fifths now.10 It has been hard for him to accept that his body is aging and he no longer needs to solve every problem by himself. I try to reassure him, usually unsuccessfully, but I also understand. My independence is fading alongside my health.

A Good Man

When my father was in a coma, my elder siblings were old enough to keep the house running, literally. We had one rotary phone, and it rang all day – neighbours, friends, church members, coworkers, and relatives from both sides, all wanting to know how my father was. So many meals were delivered, we never had to worry about food. Family friends gave us rides to visit the hospital. Cards flooded the mailbox. When my father came home, many visitors welcomed him back, including his coworkers, who came in a group. It was clear my father was respected and loved by all who knew him.

My father had many hobbies, including classic cars. But when he saw that such hobbies drained our financial resources, he set them aside. Providing for his family is his greatest concern, but he is also generous to others. He recieved a large insurance payout after his accident,11 but my parents, after fulfilling immediate needs and setting aside savings for each of us, gave most of it away to those whom they saw in need. The home my father built has, at different times, sheltered more than his family. It currently shelters three generations of his family, not for the first time.12

I grew up in evangelical and fundamentalist Christian circles, and I’ve witnessed systemic misogyny in those circles. But my father has never acted or spoken in an objectifying or denigrating way to or about women. For my father, there is only my mother, and he always acts to protect her from hurt.13 I have told how highly he values his daughters in Literature & the Single Woman. My father set such a high standard of how men can interact with women that I am always angered by those men who excuse their abusive and exploitive behaviour by calling it masculinity.

My father is a Christian by conviction. In his bachelor days, not all of his risk taking was harmless. At my parents’ wedding, one of my father’s aunts said to my mother’s mother, “The poor girl, doesn’t she know how much he drinks?” My mother laughs at that story, because the man she married was no longer a heavy drinker. The day my father believed Jesus Christ was the day he stopped his destructive substance abuse.14 The sincerity of both my father’s and mother’s faith stand in contrast to the hypocrisy I’ve seen in church and homeschooling circles. I am also a Christian by conviction.

We look nothing alike, my father and I. Once, when my siblings and I accompanied our father on a visit to his hometown, he introduced us to an old schoolmate. She immediately saw the family resemblance in my siblings, but declared, to our amusement, that she didn’t know where I had come from. My father chose my second name, so that my initials match his.15 He is also H.A.J., although those acquainted with him would never know, since he is known by an old Scottish diminutive of his second name. I am told that when I was an infant, he said, as he held me, “I could take a dozen of these.”16

When I started nursing school, it was my father who drove me to my classes at the community college, on his way to work. Later, when I went to university, he helped me move. He has driven me to airports, bus stops, and train stations, and picked me up again. He has also taken me to the hospital and waited with me in the emergency room. He never asks for thanks; he just does it. My father isn’t perfect, and neither am I. Our mental resemblance means that we can aggravate one another, but my father never stops being there for me when I need him.

Epilogue: After I read this to my father, he said, “I did all that?” Then he insisted that he couldn’t have done any of it without my mother. They mark their 50th anniversary this year.

This quote has been used in modern evangelical circles to preach financial success as a spiritual good, but the full proverb is: “A good man leaves an inheritance to his children’s children; and the wealth of the sinner is laid up for the just.” In other words, it isn’t about monetary value at all, it is about the lasting effect of goodness.

I cannot stay long outdoors, due to my asthma, so I am limited in what I accomplish.

This what my father sang when under financial pressure:

On the other hand, my father is famously absent minded on mundane matters. In the days before cell phones, my mother taped shopping lists to his steering wheel. He once brought home milk two nights in a row, because she forgot to remove the list.

No, this is not metaphorical. My father had not been arrested. The police officer truly was being hospitable.

He did not like taking the same route twice. I’m the same way.

It’s long story… I don’t know how to tell it yet.

The blind spots didn’t affect his ability to drive, he just noticed them when looking at grids of any kind, and a printed page is like a grid.

This sounds like ironic exaggeration, but isn’t. He actually used to carry around full length cedar trunks and other ridiculously heavy objects.

My parents were told they could sue the first hospital for malpractice, but they didn’t want to cause trouble for others.

Multigenerational households are normal to my father. His grandparents also lived on the family farm, and he remembers his grandmother’s baking with nostalgia.

My father would play this song, which says it all:

He doesn’t think drinking alcohol is wrong. Rather he no longer felt the need of alcohol’s mind and mood altering effects. He gave up smoking at the same time for similar reasons.

My mother chose my first name.

Apparently, I was a very quiet baby.

A wonderful portrait of a clearly remarkable man.