Lines in Black & White: The Illustrations of C. Walter Hodges

Illustrated Edition of Why is this book on the shelf?

I love black and white pictures. Any skilled blend of the visual spectrum’s two extremes, from the stark simplicity of ink on paper to the three-dimensional grayscale of black and white film1, brings joy. Perhaps it is because I first saw the world during a season when trees stand out in dark, fantastical lines against grey skies and snowy fields. In my early adolescence, I was given a book about drawing. With our low income, I couldn’t afford the recommended art materials, but I dreamt over the black and white illustrations. When I got my first paying jobs, I spent my pay on night courses, including drafting and drawing.

In the beginning, we are told, God said “Let there be light”, and there was light, and he divided the light from the dark into day and night. Humans need both, the light to live, the dark to rest. Where I dwell, light and dark wax and wane in prevalence. In winter, the cold daylight is short but snow enhances what light there is from sun, moon, and stars. In summer, the long, hot light of the growing season is tempered by the shade of leaves and short nights. Life takes place in the contrast of light and dark. It is the way we perceive everything.

I learned to read from old illustrated school readers, but I cannot remember when the printed word itself became an illustration in black and white. In my childhood and youth, I thought all those who read saw printed letters as individuals who interacted, conversed, even quarreled with one another. In adulthood, I learned not everyone has ordinal-linguistic personification, a form of synesthesia. The personalities of letters influence my spelling preferences and word choices. For example, I see grey skies as being clearer and lighter than gray skies, which are filled with heavy, dark clouds, because, to me, e has a less dominant, more easygoing personality than a. Perhaps my synesthesia explains why I find black and white story illustrations so satisfying. The illustration lines enhance the word’s pictures. There are several great illustrators in this style, but my favourite is C. (Cyril) Walter Hodges (1909-2004), British author, illustrator, and theatre designer.

The Shield Ring by Rosemary Sutcliff, Illustrated by C. Walter Hodges

My serendipitous discovery of C. Walter Hodges coincided with my discovery of the extraordinary historical novelist for young adults, Rosemary Sutcliff.2 My father had built bookshelves in nearly every room in the house, and uncategorized books filled the shelves, many of them given to us by people who were moving or downsizing. I have no idea who passed on The Shield Ring to our family, but I discovered it one day on the bookshelf next to my desk. I was supposed to be doing schoolwork, but that shelf was a constant temptation. I read The Shield Ring in snatches, hurriedly placing it back on the shelf or, if I didn’t want to lose my place, laying it open in the desk drawer, to quickly close if I heard footsteps approaching.

Initially, I did not like The Shield Ring, being a callow adolescent with a taste for obvious romance in books. At the time, I tended to read the first couple of chapters, the last few pages, and a few sections in the middle of a book to decide if I wanted to read it all. A book without an obviously romantic ending was often ditched. But Hodges’ minimal illustrations – just a small line drawing at the head of each chapter – intrigued me enough to keep reading. The unique way the book immersed me in 12th-century northern England became more interesting than the standard romance.3

The Shield Ring asks about courage, the courage to give your life for what you hold most precious. Not the courage to die in the heat of battle, but the courage to endure long, slow suffering. The kind of suffering that only ends if you betray what is precious. I was familiar with that question. The conservative fundamentalist ethos of my youth anticipated such suffering, with stories of early Christians in the arena, and Reformation Protestants at the stake, and new Christian converts in hostile countries, all leading to the question whether I could be as courageous. Sutcliff suggests you will not know the answer until you actually face such a test.4

Hodges’s simple illustrations are realistic in style, depicting the isolated and fragile world of a group of Norse settlers and Saxon refugees in England’s Lake District who defy subjugation by the Normans. The headings provide glimpses of main and secondary characters, but not in so much detail that no room is left for the mental images of Sutcliff’s text. As I read each chapter, my imagination took Hodges’ opening sketch, and, with Sutcliff’s words, filled the picture with colour, imbued it with life, and expanded it into a world where I witnessed the events of the story.

I do not have the copy that I found on the shelf – one of my siblings has it – but thanks to the internet, I found another copy with the original illustrations. It is a discarded library book, so while I am happy to have a copy, I am also sad that another young bookworm like myself cannot one day discover The Shield Ring on the library shelf.

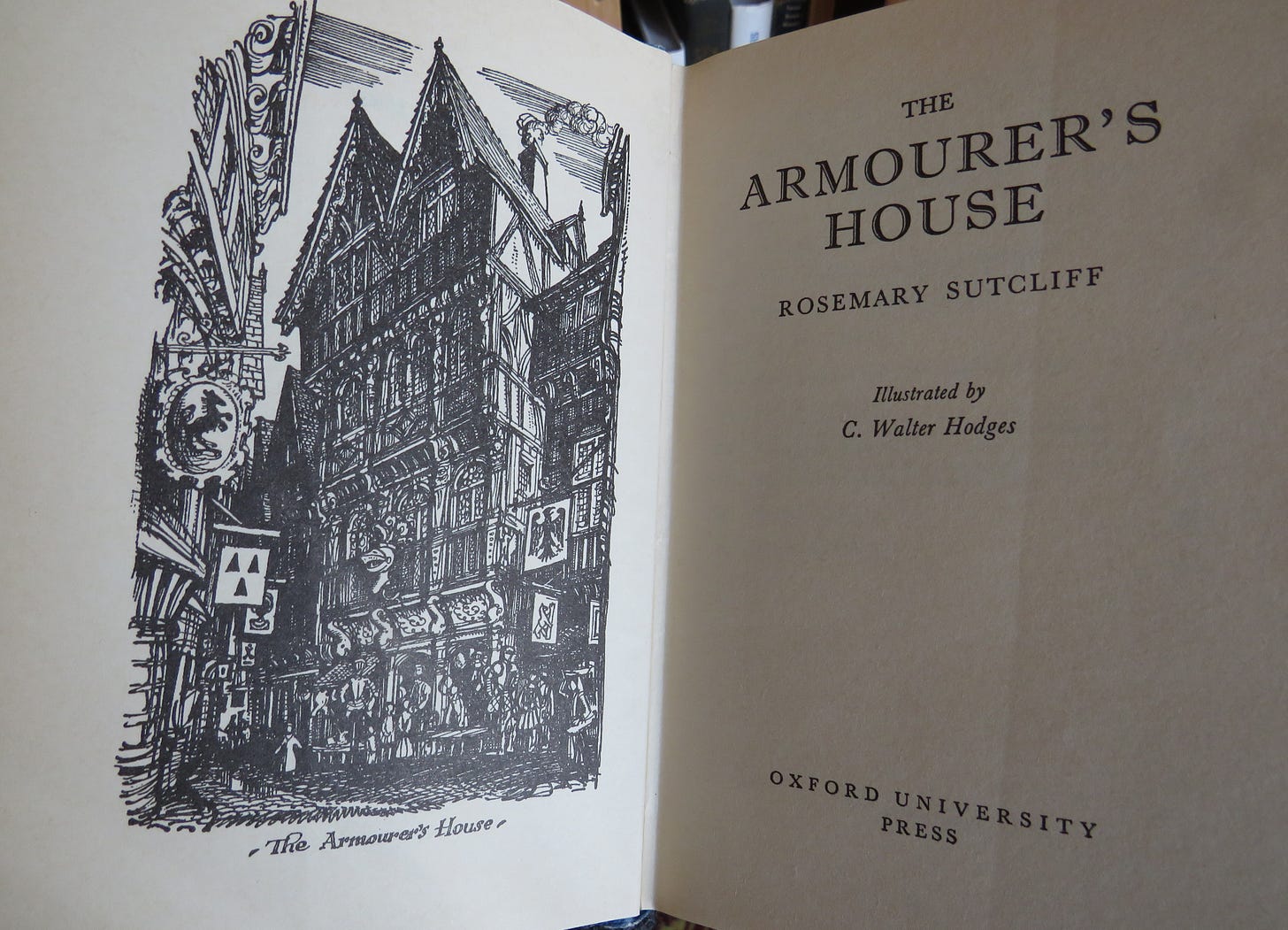

The Armourer’s House by Rosemary Sutcliff, Illustrated by C. Walter Hodges

When I bought this book, I didn’t know that C. Walter Hodges had illustrated it. I first read The Armourer’s House as an ebook. Rosemary Sutcliff’s prose was so entrancing that I had to get a physical copy. Discovering Hodges’ drawings in the printed book was icing on the cake.

The story is for a younger audience than most of Sutcliff’s work, and set in a later time period than the Roman or early medieval eras in which she usually set her stories. It is told over the course of a year in London during the reign of Henry VIII, when Anne Boleyn was his consort. But the political and religious upheaval of Henry’s reign is not Sutcliff’s focus. Her characters are the family of a master craftsman. The major events that occupy them are the seasonal festivals of English custom, while the two main characters, a young girl and boy, are fascinated by tales of English explorers, longing to sail the seven seas themselves.

Hodges’s drawings accompany the pattern of the story. He captures the mayhem of May Day, the magic of Midsummer’s Eve, and the quiet beauty of Christmas Eve. The story highlights Hodges’ versatility. His style changes to surreal for the illustration of a fairy tale told at All Hallow’s Eve.5 In an illustration of the children pretending to sail to the ‘New World’, Hodges incorporates antique map elements for a partially abstract effect. The contrast in the story between the faraway lands the children dream of seeing and the beautiful festivals that they consider customary is striking to the modern reader, who may see the two things in reverse. The old walled, half-timbered London disappeared into smoke during the Great Fire of 1666 and English customs faded under Puritanism and industrialization, while those of us now living know all too well that the tall tales of 16-century English explorers about the ‘New World’ did not reflect reality. But Sutcliff and Hodges beautifully portray another place and time, and leave any deeper conclusions to the reader.

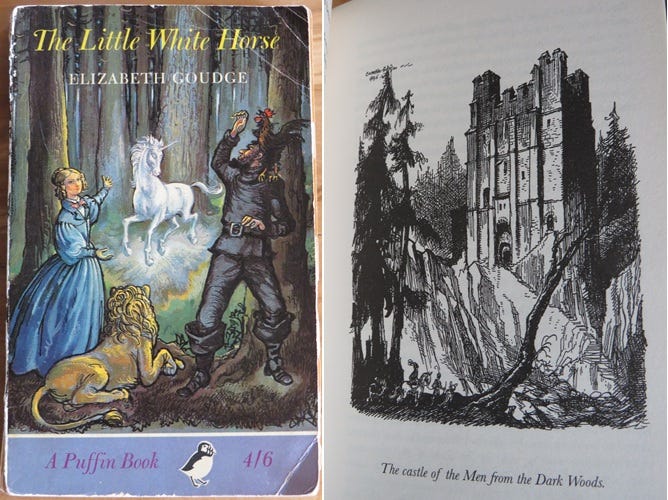

The Little White Horse by Elizabeth Goudge, Illustrated by C. Walter Hodges

In my very early twenties, in order to take night courses – and study advanced violin and music theory – I left my rural home to stay in the city. One of my uncles and his wife lived there and they generously offered me a place to stay. Their house did not have as many bookshelves as my home, but their shelves were filled with books that I had not yet read. When I found The Little White Horse, I had never heard of the author or book. It was an entirely new discovery for me. I loved the story so much that I asked to borrow the book so I could read it to my family. They loved it too.

As a child, I had a guilty secret. I loved fairy tales. The conservative fundamentalist culture in which I moved had many voices contributing to my sense of guilt. In the late 1980s and 1990s, the world was full of bogeymen to the adults around me,6 and works of fantastical imagination were deemed among the most dangerous. Whether it was those who saw sinister meaning in Disney animated films, or those who saw the devil in fairy tales, or those who declared C. S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien were gateway drugs to the occult, the message was unmistakable – the stories I liked best were sinful.

In retrospect, many of the adults who deemed fairy tales and fantasy dangerous were dealing with their own trauma, former hippies who regretted their past. Our parents were more temperate. They never set a rule against fairy tales, nor did they purge our bookshelves of all works of fantasy. It was my siblings and I, spurred on by lurid anecdotes of accidentally triggered demonic oppression, who carried out such a purge.

By my early twenties, I was readjusting my perspective. I retained a deep Christian faith, but questioned the benefit of the rules I had learned. A number of the seemingly model homeschooling families I knew with stricter rules than my family were imploding. I started to read the books I liked. The Little White Horse was so charmingly English that I didn’t recognize it as fantasy at first. Its world, where fairy tale magic and Anglican tradition coexisted, was a bit puzzling, but it worked.7 In reading it to my family, I felt free to openly enjoy fairy tales again.8

I didn’t initially recognize C. Walter Hodges’ work on The Little White Horse, as it was so different in style to The Shield Ring, but I loved the story’s pictures as much as I loved the text. Hodges made a few colour plates for the work, but it is his black and white line drawings that fit so beautifully into a story about the beauty of day and night, sun and moon. His characters match Goudge’s descriptions perfectly, while his maps of the fantasy kingdom of Moonacre equal the Narnia maps of illustrator Pauline Baynes and The Hobbit maps of J.R.R. Tolkien for clarity and charm.

I found The Little White Horse on my aunt and uncle’s shelf before Elizabeth Goudge’s work regained its current quiet popularity. So far as I knew, the copy they had was the only one I might ever read. I couldn’t find the book in the library and the few online sale listings were for highly expensive collector’s editions. My aunt died of cancer while I was in my last year of my college nursing course. When I graduated, I returned to the city to help my uncle, who had suddenly become very ill. After a month of serious illness, he died of a rare autoimmune condition. When their house was prepared for sale, my cousins told me to take any books I wanted. Among the books I chose was The Little White Horse. I have since passed along that copy to a sibling, to read to her family. But the story and illustrations in my current reprint edition still remind me of the two happy years I spent with my dear aunt and uncle.

I once attended an exhibit of the photograph portraits of Armenian-Canadian Yousuf Karsh. The black and white film was so finely developed that the photographs were holographic, as if the famous people were about to step out of their frames and speak.

Note for Sutcliff fans: The Sheild Ring is the second published (in 1956) but, chronologically, the final book in Sutcliff’s ‘dolphin ring’ books, a sequence of otherwise independent historical novels linked by the presence of an heirloom owned by a character. The Sheild Ring title refers to a protective battle formation, not the heirloom. C. Walter Hodges also illustrated the first book in the dolphin ring sequence, The Eagle of the Ninth, in 1954. I have a vintage Canadian school edition of The Eagle with Hodges’ woodcut illustrations printed small. The other books in the seqence, in chronological order, are The Silver Branch, Frontier Wolf, The Lantern Bearers, Sword at Sunset*, Dawn Wind, and Sword Song. *Sword at Sunset is a realistic retelling of the Arthurian legends and one of Sutcliff’s few books for adults - its content is mature and one of the darkest novels I have ever read.

This is very similar to the instruction that Jesus Christ gave about facing persecution, “make up your minds not to prepare your defense ahead of time…” (Luke 21:14-15).

The fairytale told is Tamlin, one of multiple variations in English folk tale and song about fairy-led hostage takings or kidnappings. English fairy tales are often recognizable for their somewhat sinister quality, and the English fairy is usually a mischevious and/or malevolant being. The only fairy tale I remember being terrified by as a child was the English folktale ‘Tom-Tit-Tot’ - the English variant of Rumpelstiltskin - which I found in an old school reader.

Combining English magic and Anglican custom is a recurring feature of great British female fantasy authors. Diana Wynne Jones has a magic-working Reverend in her multiverse version of an English village in the final Chrestomanci book, The Pinhoe Egg. In Susanna Clarke’s alternate history fantasy Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell and short story collection The Ladies of Grace Adieu, both magician and clergyman are possible gentlemanly professions in the Regency era.

I finally read Tolkein’s magnum opus at my uncle and aunt’s, since we had purged our LOTR copy before I was old enough to read it. At the time, the Peter Jackson films had been recently released, and the film posters were very intriguing; but I found the books, and the films, disappointing. I knew The Hobbit from childhood, from before the purge, and far preferred it to its sequel.