Medical Memory: Three Memoirs & a Family History

Why is this book on the shelf? Limited Reviews VI

“Progress, far from consisting in change, depends on retentiveness. When change is absolute there remains no being to improve and no direction is set for possible improvement... Those who cannot remember the past are doomed to repeat it.” – George Santayana, Reason in Common Sense, 1905

This review is dedicated to the memory of my Great-aunt Beatrice.

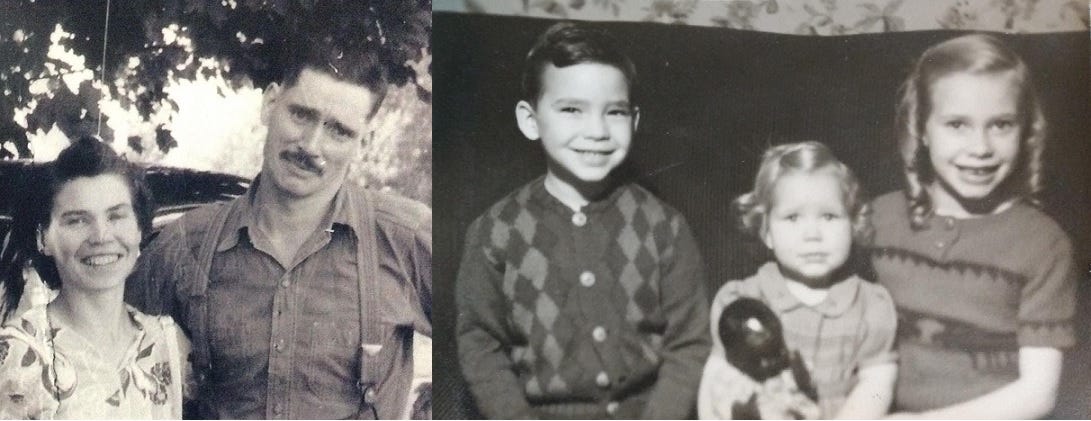

I am the first person in my family line to hold a professional degree in healthcare, but I am not the first to have worked in healthcare. My great grandfather, father of my maternal grandfather, was a surgeon’s assistant in a Rail Road Hospital somewhere in North America during the late 1800s. In his bachelor days, Great-grandpa J. P., was a rolling stone that gathered no moss and a jack-of-all-trades. Surgeon’s assistant was only one of several occupations at which J. P., an English migrant, tried his hand. But we have photographic evidence for his stint as surgeon’s assistant.

J.P. eventually took as his bride a young woman from England. The family story goes that J. P.’s wife, Alice, was ostracized by most of her upper crust family for marrying a man “from the colonies”. Certainly neither J.P. nor Alice had any local connections when they settled and raised a family in Canada. I grew up hearing the stories of my ancestors again and again, with different witnesses telling and retelling their recollections, until the past became alive with breathing, feeling humans. That sense of a living past is why I have multiple eyewitness histories and memoirs on my shelf. Several of those memoirs are about those who worked in healthcare when my great-grandparents were alive.

The Horse and Buggy Doctor by Arthur E. Hertzler, M.D.

One of the most tattered books on my shelf is the medical memoir of a physician who was practicing around the same time that my great grandfather was a surgical assistant. I first discovered the memoir on my father’s cluttered basement shelves amongst a miscellaneous lot of old books, and read it in my teen years, when I daily dreamt of becoming a doctor. The book was published in 1938, when Dr. Hertzler was approaching the age of 70. He was both a physician and surgeon, studying first in the U.S. and later in Germany, and practiced in rural Kansas, eventually founding a hospital.

The book begins with a chapter titled ‘Medicine as it was in my boyhood’, opening with Hertzler’s childhood recollection of a neighbouring family losing seven of their eight children to diphtheria within days. He describes, based on his own medical experience, the agonizing way diphtheria toxin suffocates a child. His description is more clinical than L. M. Montgomery’s novelized depiction of Jims suffering from diphtheria croup in Rilla of Ingleside, but both convey the horror of the once dreaded childhood disease.1 Diptheria is now prevented through routine childhood vaccination.

In the rural farming area where I grew up, old graveyards at the corners of farm fields bear witness to a terrible historical death rate among children, with stone after stone attesting to the brief lives of those buried beneath. My father has ancestral records of his settler family going back over two centuries, and he observed a pattern of children being named after older siblings who had already died. My maternal grandfather, J.P. Jr., was named after an older brother who did not survive.2 Dr. Hertzler writes that after tending his own daughter through life threatening febrile seizures, he could no longer attend a child’s sickbed, saying after thirty years the memory still haunted him.

Hertzler tends to ramble, organizing his book by theme rather than chronologically. Reading his memoir is like listening to a garrulous old man reminisce about his younger years. His stories show not only compassion and professional scientific interest, but also a keen and irreverent sense of humour. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, scientific study came into direct conflict with religious tradition. Hertzler was firmly on the side of science, tending to be scornful of religion. But the religion he scorns is also characteristic of that era – revival preachers who railed against sin in public but were immoral in private; or adherents of self-healing movements like Christian Science or New Thought, which were growing in popularity during the decades he practiced.

Dr. Hertzler tells the story of surgically removing a large abdominal tumour from a patient while listening to a friend of the patient constantly tell the patient’s family member that the whole thing was a figment of the imagination. Thoroughly exasperated by the end of a difficult surgery, he dropped the tumour at the feet of the friend, responding to her horrified reaction by repeating back her words about it being all in the imagination.

In his final chapter, ‘Medicine as it is now’ Dr. Hertzler concludes:

“In summary let it be emphasized that the freedom from disease that the public now enjoys is the result of the labor of the regular profession. It is all right for those with minor ailments, or with none at all, to consort with the cultists. It is all right to do fool things if someone is standing by able to protect us from the fruits of our folly. But, let it be emphasized, if the cultists inherited the earth the epidemic diseases would be upon us with their original pristine terribleness. After more than sixty years I can still hear the eloquent prayer that filled the countryside when epidemics of diphtheria appeared. One tube of antitoxin will do more good than all of these. I have seen all of these things.”3

Pioneer Preacher by Opal Leigh Berryman

In her introduction, Berryman states she wrote her book to show that there were good men in the era of the Wild West, among them her father, the Reverend George C. Berryman, a Baptist minister. She compresses the events of ten years into a narrative span of two, beginning in 1905 when she was eight and arrived with her father and mother at the Llano Estacado in West Texas. There her father, a Baptist minister, was to plant a church. Names and identities of people are changed, but she affirms that all events in the book actually happened.

Many of the narrative threads she weaves through the book might seem part of the Wild West. A sheriff seeks out Rev. Berryman’s help in hunting down a brutal murderer. A widowed rancher’s beautiful daughter is sent to Mrs. Berryman to learn to be a lady, drawing after her the cattlemen who vie for her attention. An oily itinerate preacher pressures Rev. Berryman to hold revival meetings and tries to steal his church. A suave newcomer uses his unsanitary dental practice as cover for selling liquor and hosting card games. A respected rancher takes advice from the Reverend in dealing with cattle rustlers. But then, truth is stranger than fiction.

Opal Berryman’s reminiscences are by turns comical, sentimental, and tragic. Her father is concerned for both the spiritual and physical health of his flock. The entire community is devastated when a child dies of rabies because it took too long to procure a vaccine. Later, the Reverend welcomes an immigrant physician to the community who is researching tuberculosis, a disease that many sufferers went west to cure.4 When travelers bring smallpox to the community, Rev. Berryman assists the physician in nursing the sick and tries to persuade reluctant townspeople to be vaccinated by having his own family vaccinated. Opal Berryman recounts her childhood misadventures with wry wit, including a severe but temporary reaction to the smallpox vaccine.

Despite success in stopping the spread of smallpox, sinister and shadowy figures start a campaign of threats and intimidation against the physician, who, due to his Armenian origin, is presumed to be of African descent. Opal Berryman remembers an evening spent in happy celebration around a community Christmas tree in the local schoolhouse, but when everyone prepares to go home, a burning cross flares up out of the darkness on the edge of town. Her father, who preaches against hatred and intolerance, determines to search out and confront the perpetrators.

Opal Berryman published Pioneer Preacher in 1948, and she recounts conversations she heard as a child with the vocabulary that was used, including the n-word. The offensiveness of the language testifies to the ugliness of the racism and prejudice. Some of the local Ladies Aid who meet with Mrs. Berryman are more interested in determining pedigree and social status than serving the needy, wanting to arbitrate who should be welcomed to the community and who should be shunned out of town.

My upper crust great-grandmother Alice, who was about the same age as Mrs. Berryman and her peers, tried to be the arbiter of acceptance in her family. When her only son, my maternal grandfather, J.P. Jr., married Vi, from a family of working class English immigrants, Alice was displeased. Vi’s physical appearance – black hair, broad nose, and wide mouth – was genetically suspect. Alice snidely told Vi that she would have no trouble having children because women with wide mouths had an easy time giving birth, Vi retorted, “Oh, is that how babies are born?” “Don’t be smart,” Alice snapped back.5 When Vi’s eldest son was born with black curly hair, Alice declared it was evidence that Vi’s family had, and I quote, “Gypsy blood”. Broad noses and full-lipped wide mouths continued to appear among J.P. Jr. and Vi’s subsequent offspring, but, in 1950s urban Ontario, the family facial features led to nothing worse than petty bulling at school – my mother was called “liver lips” by classmates. J.P. Jr. and Vi’s children were quite intrigued at the suggestion they might have Romani ancestry, but genealogical research has not shown any connection.

In 1900s West Texas, Rev. Berryman finds that the ringleader of the threats is a man with a social climber wife, who is trying to conceal his own Creole ancestry. The Reverend sharply reproves the man, demanding that he disband his gang of intimidators and apologize for his actions. The physician is able to continue his work. Opal Berryman’s narrative bears witness to the forgotten who did oppose the ignorance and intolerance of their time in history.

‘Father looked down on me, smiling from one side of his mouth.

“Unfortunately, the world is full of distorted information. Sometimes it is difficult to sift out the truth from exaggerations or distinguish it from pure fabrication.”

“But how can you tell?” I wanted to know.

“You can’t, but you can reserve judgement until you have more information, or await developments.”’6

The Gift of Pain by Dr. Paul Brand & Philip Yancey

When I declared I wanted to become a doctor, at the age of twelve, my family started giving me books about and by doctors. Among these were the collaborations between eminent leprosy specialist Dr. Paul Brand and Christian author Philip Yancey, Fearfully and Wonderfully Made, In His Image, and The Gift of Pain.7 While stories from Dr. Brand’s professional experience are used in all the collaborations, The Gift of Pain is not only a meditation on the meaning of physical pain, but also a memoir of Dr. Brand’s life and work.

Paul Brand was the son of a missionary couple in the isolated Kolli Malai in southern India. His parents were not physicians but had some basic medical training required by their mission. During the 1918-19 influenza pandemic, Dr. Brand remembers his parents doing what they could to provide nutrition and hydration for the many sick and dying. Brand took his medical training in London during WWII, learning reconstructive surgical techniques while helping burned fighter pilots and wounded soldiers. After the war, he returned to India, with his pediatrician wife and their two children, to work in a medical college and hospital in Vellore.

While at Vellore, Dr. Brand was drawn to work with leprosy patients. The bacteria causing leprosy had been discovered and the new antibiotics were able to stop the active disease, but even after active infection was stopped, the patients were left with debilitating effects – foot ulcers that did not heal, fingers that shortened, hands that were partially paralyzed, and disfiguring facial scars. Dr. Brand set out to alleviate those effects.

Gradually, as Dr. Brand and his team treated and observed these patients, they realized the cause behind the apparently unhealing foot ulcers and shortening digits was that leprosy patients were injuring themselves without realizing it. The leprosy infection had permanently damaged their nerves so they felt no pain walking on a sore spot or working with an injured hand. Without pain, they could not feel to protect the weakened places on their hands and feet. Repeated injuries led to wound infections, and untreated infections led to shortened digits.

We are now more familiar with the effects of nerve damage as a complication of diabetes. When Dr. Brand came to work at the leper colony in Carville, Louisiana, in the 1960s, his interactions with American physicians led him to observe that diabetic patients were showing similar symptoms of painlessness. His suggestions were confirmed by research – diabetics develop foot ulcers because high blood sugar damages their nerves, so they do not feel when their feet are injured and infected.8 In my nursing career, I have only once encountered a former leprosy patient; but I have treated many diabetic neuropathy patients, often applying to their ulcered feet a pressure offloading cast similar to the ones originally developed by Dr. Brand and his colleagues for leprosy patients. His work was such an inspiration that The Gift of Pain has always accompanied me on my volunteer nursing journeys.

“We could not ‘save’ leprosy patients. We could arrest the disease, yes, and repair some of the damage. But every leprosy patient we treated had to go back and, against overwhelming odds, attempt to build a new life. I began to see my chief contribution as one I had not studied in medical school: to join with my patient as a partner in the task of restoring dignity to a broken spirit. That is the true meaning of rehabilitation.

“Each of our patients was acting out a lead role in a personal drama of recovery. Our mechanical rearrangement of muscles, tendons, and bones was but one step in rebuilding a damaged life. The patients themselves were the ones who traveled the difficult path.”9

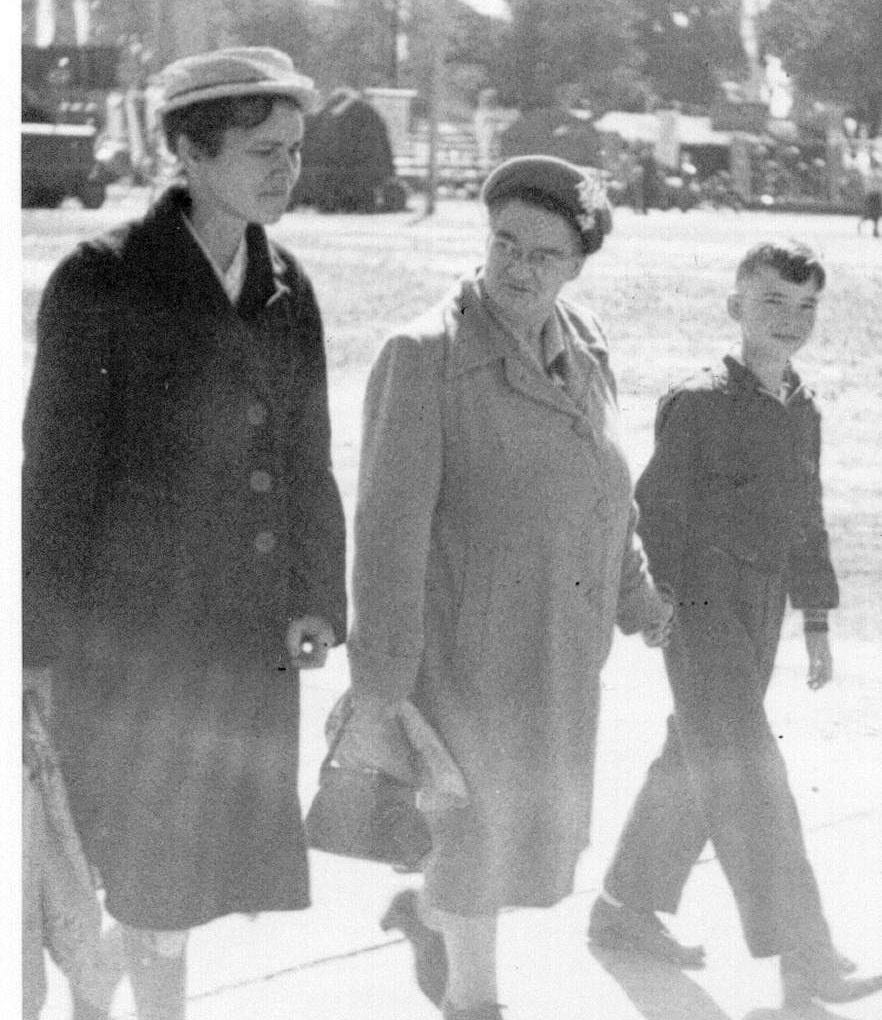

My great grandparents, J. P. and his wife Alice, had one surviving son, my maternal grandfather, J. P. Jr., and three surviving daughters. Two of my grandfather’s sisters were alive during my childhood, but his eldest sister, Aunt Bea, I knew only by reputation. Aunt Bea died when my mother was an adolescent, but her nieces and nephews all remembered their aunt vividly. They often told how, when there was any discussion about what to eat, Aunt Bea would declare, “A glass of water and a crust of bread are good enough for me.”

I am the only single woman in three generations on my maternal grandmother’s side, but on my maternal grandfather’s side, Aunt Bea was the only single woman in her generation. As I related in my review ‘Literature and the Single Woman’, there was a time when my mother expected to be a lifelong single. During that time, some of her siblings, exasperated with her shyness, declared she would end up like their Aunt Bea. It was a thoughtless thing to say. Unlike myself and my mother, Aunt Bea was considered physically ineligible for marriage.

When she was entering puberty, Aunt Bea suffered a then common childhood illness, mumps. Mumps is a virus that usually infects the salivary glands of the mouth, causing the characteristic swollen face and neck. But the virus can also infect other organs, including the ovaries and testes. These essential sex organs may be so badly damaged by the infection that sterility results. As my mother delicately put it, because of the age at which she had mumps, Aunt Bea never developed physically as a woman. She never experienced any of the bodily changes of female puberty.

Aunt Bea became a nanny for well-to-do family. The letters she wrote to her brother, while he served overseas during WWII, show she dearly loved the children in her charge. But there came a time when the family no longer needed Aunt Bea. Her father, J.P., had passed away and her widowed mother, Alice, now lived with her son and his family. So, Aunt Bea came to live with them too. While her nieces and nephews remembered Aunt Bea’s acid tongue and dour personality, they also recognized her sadness. She suffered internal pain and it was discovered she had cancer. In the early 1960s, cancer treatment was still limited. During the brief period before her death, my mother says Aunt Bea found peace and comfort in Jesus Christ.

The ‘Why is this book on the shelf?’ review series is about the books I keep on my very limited shelf space. Previous entries may be seen here, here, here, here, and here.

The vaccine against diphtheria was first developed in 1926. Diphtheria antitoxin is used to treat active diphtheria infection.

It was not the only child loss J.P. and Alice suffered – on an internet archive search, I came across a birth registry that listed them as mother and father of an infant girl, born dead. J.P.’s profession in the registry was listed as ‘Baker’s assistant’.

Arthur E. Hertzler, M.D. The Horse and Buggy Doctor. 1938. New York: Harper & Brothers. p. 321-322.

O. Henry’s short stories set in the West of this same period abound with references to the TB cure, for example: Hygeia at the Solito.

In the last few years of her life, Alice had multiple strokes that left her physically and mentally debilitated. Vi was the one who fed, cleaned, changed, and cared for Alice until her death.

Opal Leigh Berryman. Pioneer Preacher. 1948. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company. p. 85.

The first two books have since been updated and republished together as Fearfully and Wonderfully: The Marvel of Bearing God’s Image.

Unfortunately, diabetes patients have a harder time healing than leprosy patients. Other than the lack of pain signals, leprosy patients that no longer have active infection are generally healthy, so their wounds have adequate circulation to quickly heal once the damage is stopped. But the high blood sugar of diabetes also damages blood vessels, meaning that diabetic wounds may have inadequate circulation for healing.

Paul Brand & Philip Yancey. The Gift of Pain. 1993. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House. p. 159.