“Now these three remain: faith, hope, and love—but the greatest of these is love”1

My birth year is iconic in literature. Although the actual year did not resemble Orwell’s fictional one, I was born into a dystopic world still shivering under the threat of global nuclear war, while splinter conflicts killed millions in places less wealthy and secure than the land of my birth. My mother and father made no attempt to hide that world from us. During the day, we listened to a classical music station, but in the evening, my mother turned the radio dial to hear ‘The World at Six’ from the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation [CBC]. After the half hour newscast, we continued listening to ‘As It Happens’, a weeknight series of interviews around the world of eyewitnesses, experts, public figures, and participants in both serious and lighthearted current events.

There was a large world map on the wall of the dining room. It was placed there by my father, who had, in his bachelor years, compiled binders of facts and statistics on the nations of the earth. When a country was named in the broadcasts, my father turned from our supper table to the map and located it. He might also recall any current and historical facts he knew about the country and its surrounding region. My mother’s gentle heart was always empathetic for the humans caught in dark events. Those weekday suppers were an informal classroom, although neither of my parents deliberately decided to teach us geography that way.

I have memory fragments around the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. My clear memories of world events begin with a broadcast of the CBC’s Jerusalem correspondent reporting live from Tel-Aviv as Scud missiles from Iraq fell on southern Israel during the First Gulf War (1990-1991). It was as if I could see the night sky split by the flash and blast of the missiles on impact. A decade later, I envisioned the words of a CBC New York correspondent as he witnessed the World Trade Center towers burning and collapsing on 9/11/2001. Without television or a subscription to a national news print publication, I would not see images of events until we got the Year Book from World Book Encyclopedia, a subscription my parents managed to afford. Spoken words were the medium by which I learned to see the world. Written words taught me to love its people.

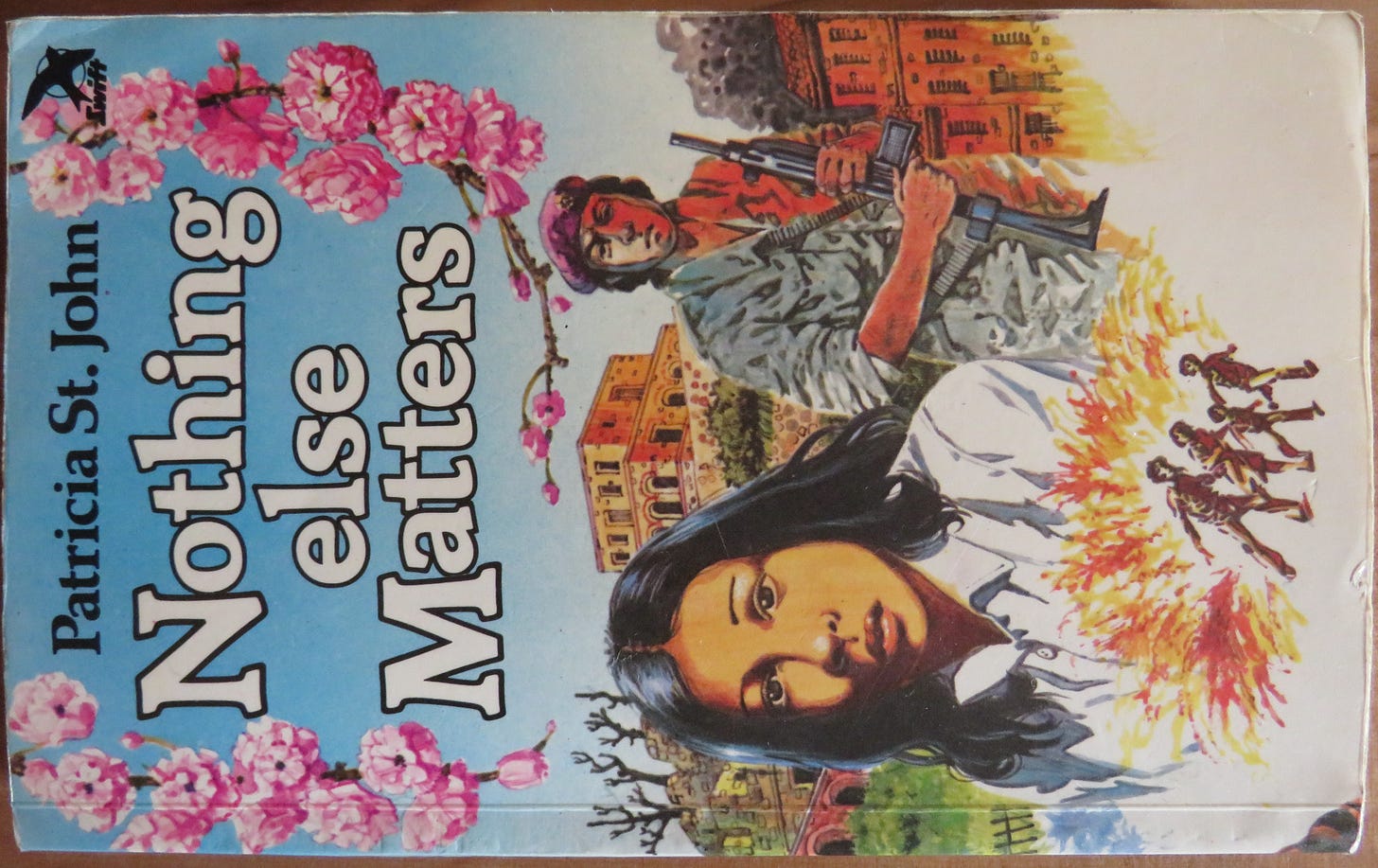

Nothing Else Matters by Patricia St. John

“Love was the only path to peace and nothing else mattered.”2

When I was ten, my Sunday School teacher gave me Nothing Else Matters by British author Patricia St. John, the Enid Blyton of evangelicals. A missionary nurse, St. John set her books in varied locations – England, Switzerland, North Africa – but with the same formula. Children misbehave and get into difficulties, adults tell them about Jesus, the children trust Jesus, correct their wrongdoing, and all ends well.3 But Nothing Else Matters did not follow the formula.

The novel is set in modern Lebanon, centring around 16 year old Lamia and her Maronite Christian family. Elias, her father, is a shopkeeper; Rosa, her mother, is a devout housewife. Lamia has a younger brother and sister, and a twin brother Amin, who is a member of a Maronite political party.

The Maronite Church is an autonomous Eastern church, begun by followers of 4th/5th century hermit Marun and in communion with Rome since the Crusades. The Maronites of Mount Lebanon have a long history of militant autonomy, fending off both the Byzantine empire and the Arab Muslim caliphates during the Middle Ages, and asserting independence from the Ottoman empire. Maronites are the largest Christian group in modern Lebanon.

Nothing Else Matters opens with Lamia’s family living quietly in a Beirut suburb as tensions simmer between Lebanon’s various ethnic and religious factions. After civil war begins, Amin is betrayed by a schoolmate whom he considered a friend despite their ethnic and religious differences. As a result, Amin is kidnapped and murdered. Devastated, Lamia longs for revenge.

The preface of Nothing Else Matters states all major incidents are based on real events. Although the story is vague on specific dates and locations, those who know Lebanese history will recognize the period of 1975 to 1976:

the Maronite Phalange murdering 27 Palestinian refugees on a bus (April 1975);4

initial fighting between the Palestinian Liberation Organization [PLO] and Maronite militias followed by an uneasy ceasefire (June 1975); 5

opening of hostilities between Lebanese Muslim and Christian militias (August 1975) - artillery barrages by both sides from highrises destroy Beirut;6

the rape and massacre of hundreds of Maronites in Damour by the PLO in retaliation for the rape and massacre of hundreds of Palestinians in the Karantina district by the Phalange (January 1976);7

the siege of Tal al-Za’tar refugee camp and subsequent massacre of thousands of Palestinians by the Maronite Lebanon Front (August 1976).8

I recognized the pattern of escalating retaliation between neighbouring groups. In the 1990s, I heard news reports of similar death spirals from Columbia, Congo (DRC), Kashmir9, Liberia, Somalia, and Northern Ireland. The year I turned 10, the hit song was Zombie by the Irish rock group, The Cranberries.

Although my family was Canadian and Baptist, the long conflict of Catholic vs. Protestant in Ireland was relevant. For three centuries, both Irish and Scots-Irish took refuge in Canada – among them my father’s ancestors.10 Some brought their quarrel with them. Historically, the annual St. Patrick’s Day parade in Toronto, Canada’s largest city, was for Catholic Irish and was often a catalyst for violence. Within my childhood memory, Orangemen, the same Protestant loyalist order as in Northern Ireland, held their own parades.11 Even the rural century towns near where I grew up displayed division, with multiple Protestant edifices within town limits, while Catholic churches stood in farm fields kilometres outside town.

At the Independent Baptist church we attended, a prominent family wanted the church to change denominations because they admired the Free Presbyterian minister leading the militant Protestants in Northern Ireland.12 I remember my parents being perplexed by such support for a violent political faction. I was slowly memorizing the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus Christ’s words recorded in the Gospel of Matthew:

“Blessed are the peacemakers: for they shall be called the children of God.”;

“Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them which despitefully use you, and persecute you”;

“But if you don’t forgive others, your Father will not forgive your offenses.”;

“Not everyone who says to me, ‘Lord, Lord,’ will enter the kingdom of heaven, but only the one who does the will of my Father in heaven”13

In Nothing Else Matters, Lamia’s mother, Rosa, gently opposes the chaos and cruelty around her. An uneducated woman in an arranged marriage, Rosa’s simple faith in the Christ who died because He loved teaches her how to live. She shelters, at different times, Christian, Palestinian, and Druze fleeing violence. Her wisdom and courage save her family from massacre. When Rosa is killed in a drive-by shooting, Lamia must let go of her hatred before she can follow her mother’s example of selfless love. Nothing Else Matters ends in hope – not for Lebanon’s immediate future, which saw 15 years of civil war from 1975 to 1990 – but hope that those quietly living faithful lives, loving even their enemies, will eventually make a difference, even in a land devoid of peace.

Patricia St. John wrote for a 20th century evangelical audience. Some of her word choices may give offense – attempts by her evangelical publishers to update St. John’s writing only flattened it into lifeless prose.14 She clearly cared deeply about the people of Lebanon; Christian, Muslim, Druze, and Palestinian – all are portrayed as complicated, believable, understandable humans. Nothing Else Matters is St. John’s best work. My copy was printed in 1983 and I cannot find any recent editions of the book, also published as If You Love Me, except a misprint-riddled independent reprint.

The story left me with a lifelong concern for the peoples of the Middle East. In university, one of the electives I took was History of the Modern Middle East. I read how the French, during their post-WWI Syrian Mandate, separated Lebanon from Greater Syria for their Maronite allies, but included territory, mostly inhabited by Muslim groups, that was not historically part of Mount Lebanon.15 At independence, a confessional system gave precedence to Maronites in the legislature, brewing discontent among the Lebanese Druze, Sunni, and Shia, with added pressure from the Palestinian refugee camps after the 1948 Nakba, leading to tensions boiling over in 1975.16

In October 1976, Syria negotiated a ceasefire that left a Syrian presence in Lebanon until 2005. In 1982, the Israeli Defense Force [IDF] invaded Lebanon to confront the PLO. Due to international pressure, the PLO left Lebanon. The IDF, under Likud defense minister Ariel Sharon, allowed the Maronite Phalange into the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps, resulting in a massacre of thousands of Palestinian civilians.17

A Lebanese Shiite militia, Hezbollah, funded by Iran’s 1979 revolutionary government, rose to prominence. The Taif Agreement of 1990 brought some peace to Lebanon, dividing the legislature evenly between Christians and Muslims. The militias disarmed, except Hezbollah. After Syrian forces left Lebanon, the IDF again invaded in 2006, this time against Hezbollah.18

When the Arab Spring failed, Syrian refugees increased the population of Lebanon by 1.5 million. The Lebanese economy collapsed. Then in 2020, a harbour explosion devastated Beirut. I remember all this when I hear of Lebanon in current news. Then I pray for mercy, justice, truth, and peace for all its people and those in neighbouring nations.

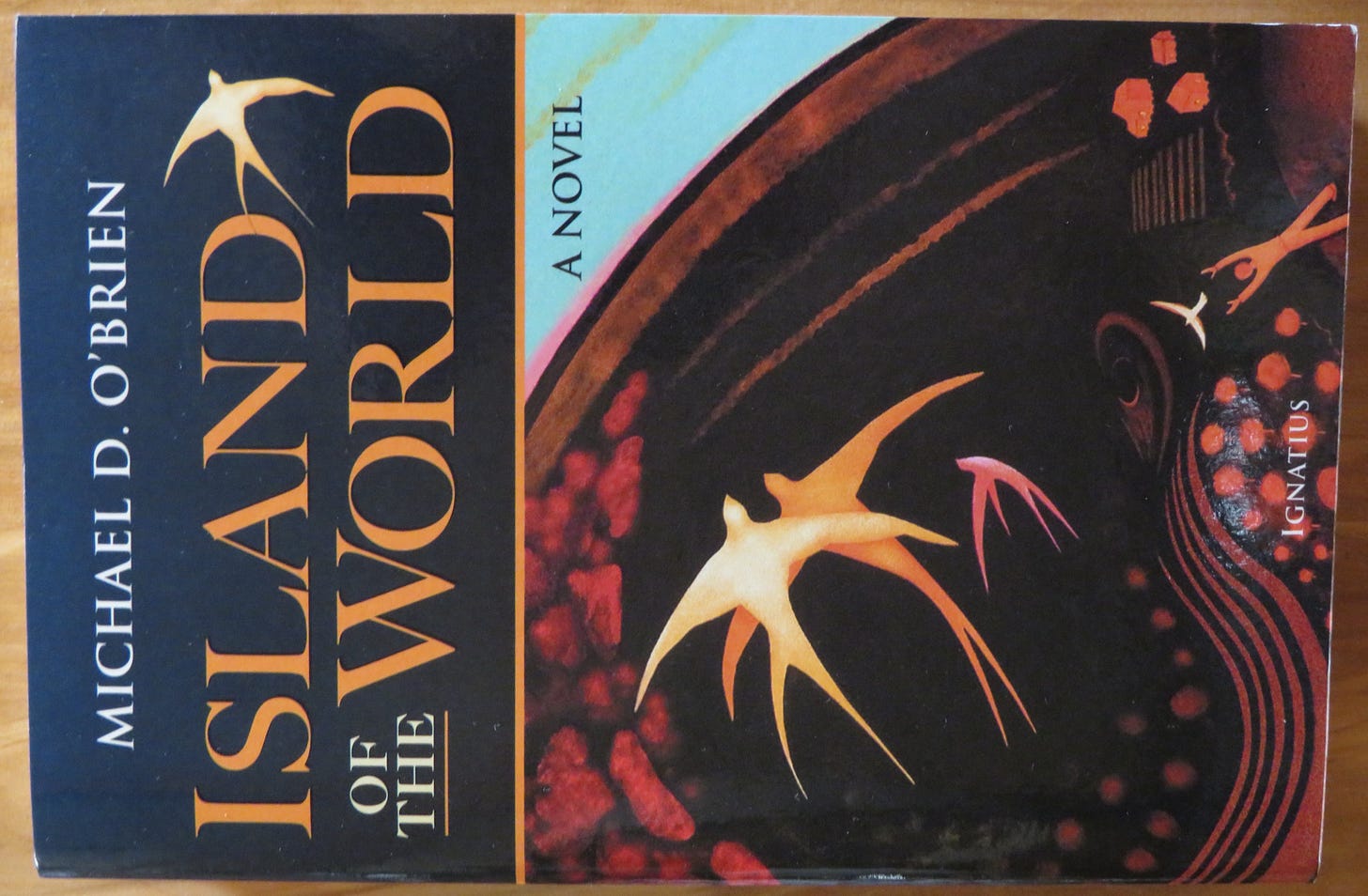

Island of the World by Michael D. O’Brien

“We come to know that love is the soul of the world, though its body bleeds, and we must learn to bleed with it.”19

Years ago, while bookstore browsing, I picked up then bestseller The God Delusion by Richard Dawkins. Opening it at random, I read: “‘Love thy neighbour’ didn’t mean what we now think it means. It meant only ‘Love another Jew.’”20 I put the book back, remembering an incident in Luke’s Gospel: A Jewish lawyer is debating the command ‘Love your neighbour’ with Jesus Christ. The lawyer asks, “Who is my neighbour?” Jesus tells a story of a Jewish man who is attacked by thieves while traveling and left for dead on the roadside. A Jewish priest and Levite passing by both ignore the man. A Samaritan stops, takes the man to the nearest guesthouse, bandages his wounds, and pays for his care. Jesus asks the lawyer, “Which one was the man’s neighbour?”

The record of Kings in the Hebrew Bible tells how the brutal Assyrian empire ethnically cleansed the northern kingdom of ancient Israel, Samaria, and resettled Samaria with tribes from the region of Babylon (modern day Iraq). These settlers stayed in Samaria, syncretizing Judaism with their own religions. The syncretism of these Samaritans was abominable to the historian of Kings, a view that was still held by Jews – descendants of Israel’s southern kingdom, Judah – during the Roman empire. Even Jesus Christ’s followers were intolerant. After a Samaritan village declined to host Jesus, his disciples asked to call fire from heaven to destroy it. Jesus condemned their request. When Jesus told the parable of the Good Samaritan, he was deliberately provocative.21 ‘Love thy neighbour’ means ‘love your enemy’ too.

During the pandemic of 2020-22, I worked as a community nurse. On days off, I was emotionally and mentally exhausted. But each year, I tried to read at least one new novel and one non-fiction work. The novels were by Michael D. O’Brien, Catholic Canadian iconographer and author. I read most of his Island of the World in spring 2021, while I was recuperating from surgery. The pause gave me the emotional space the book needed.

The novel follows the character of Josip Lasta, beginning with his childhood in the Balkans near the end of WWII. His Croatian parents are murdered by Communist Partisans. Sheltered by his aunt, who married a Partisan, Josip grows up in Yugoslavia. In university, his association with an intellectual group triggers the paranoia of the authorities and Josip is arrested.

My mother’s instinctive humanity made her turn on the news every evening, but sometimes, it made her turn it off again. She could not endure descriptions of brutality against humans. Details from murder trials or unfathomable atrocities like the 1994 Rwandan genocide were curtailed, but we heard enough to shudder at the colossal inhumanity that humans could display to each other.

The beginning of Island of the World conveys the chaotic bloodshed that engulfed soldier and civilian, male and female, old and young, in the Balkans during WWII. Similar brutality occurred throughout Eastern Europe, as partisan groups opposed the Nazis and/or the Soviets. The Balkan war entangled Communism vs. Fascism with older ethnic and religious divisions. Catholic Croat, Bosnian Muslim, Orthodox Serb – all groups included both perpetrators and victims. Few of the Jewish population survived, nearly none of the Roma. The carnage was so hideous even the Nazis were disturbed by their terrorist ally, the Ustashe; and the post-war Communist regime in Yugoslavia buried certain actions by the Partisans in secrecy.22

Josip eventually finds asylum in a cosmopolitan city in the West. He lives in obscurity, known only to a handful of diverse neighbours to whom he seeks to be kind, although some are easier to love than others. Inwardly, Josip wrestles with forgiveness, both of those who killed his family and tortured him, and of himself, for surviving while others died. His wounds reopen when, after the Communist bloc of Eastern Europe dissolves and his homeland declares independence, another cruel ethnic war begins.

As an adult, it is strange reading historic events in textbooks or historical novels that I first heard reported in the news. When the Cold War ended, even I, a young child, sensed the optimism. As each former Communist country in Eastern Europe seemed to embrace democracy and freedom, hope for peace increased in the West. The euphoria is audible in German band Scorpions 1991 hit Wind of Change.

My father has often quipped the worst part of a long life is all the déjà vu. His suppertime commentary linking historic and currents events encouraged me to read history for myself. The cruel past was near to my childhood present – I had an uncle and great uncle who survived the Holocaust.23 I remember journalists describing pieces of the 1992-95 genocide in Bosnia: Serbian snipers shooting civilians on the streets of Sarajevo; the rape and massacre of Muslims in Srebrenica; a concentration camp in Omarska.

I listened throughout the 1990s as the former Yugoslavia became Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Kosovo, North Macedonia, Serbia, Slovenia – Montenegro in 2006. While I was studying nursing a decade later, one of my instructors was from Serbia, while a fellow student was of Bosnian origin. They intentionally and thoughtfully discussed the recent past.

When I finished Island of the World, I said it was the most beautiful book I had ever read. The narrative is in the present tense. The reader shares each moment with Josip, learning with him, only understanding his story by remembering, as Josip does, what has already happened. The vivid mental images the words paint make the story both wonderful and painful to read. O’Brien portrays the human person as an island, alone in our agony and experience, love our sole connection to the world.

Final line of I Corinthians 13

Patricia St. John. Nothing Else Matters. 1983. Bristol: Purnell and Sons.

N.B. I liked St. John’s books in childhood - my favourites were Treasures of the Snow and Star of Light. Enid Blyton was also entertaining. But they were formulaic.

William L. Cleveland & Martin Bunton. A History of the Modern Middle East, 6th Ed. 2016. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

ibid.

ibid.

A ‘both sides’ account of the events leading up to and during the Damour Massacre is here: https://truthandreconciliationlebanon.org/en/damour/.

Cleveland & Bunton. A History of the Modern Middle East.

The award-winning 1999 Hindi-language film, Mission Kashmir, appealed for love to end the violence.

N.B. My paternal ancestors emigrated in the mid-1700s; the family legend is: “they were kicked out of Scotland for stealing sheep, so they came to Northern Ireland, but they got kicked out of Northern Ireland for stealing sheep, so they came to Nova Scotia, and there weren’t any sheep to steal, so they stayed.”

When Charles Dickens visited America in 1842, he briefly visited Toronto in (then) Upper Canada, writing in American Notes: ‘It is not long since guns were discharged from a window in this town at the successful candidates in an election, and the coachman of one of them was actually shot in the body, though not dangerously wounded. But one man was killed on the same occasion; and from the very window whence he received his death, the very flag which shielded his murderer (not only in the commission of his crime, but from its consequences), was displayed again on the occasion of the public ceremony performed by the Governor General, to which I have just adverted. Of all the colours in the rainbow, there is but one which could be so employed: I need not say that flag was orange.’

N.B. The church didn’t change denominations, and the family eventually left. But years later, a new pastor briefly preached at the same church and talked at length, from the pulpit, about his deep admiration for that same Free Presbyterian minister.

N.B. If buying St. John’s books, look for copies printed before 2000.

George Antonius. The Arab Awakening: The story of the Arab National Movement. 1939. US: Allegro Editions.

Cleveland & Bunton. A History of the Modern Middle East.

ibid. Note: An Israeli government investigation found Sharon “indirectly responsible” for the massacre.

ibid.

Michael D. O’Brien. Island of the World. 2004. San Francisco: Ignatius Press.

Richard Dawkins. The God Delusion. 2008. New York: First Mariner Books.

References: II Kings 17 (origin of Samaritans); Luke 10:25-37 (Good Samaritan); Luke 9:51-56 (Samaritan village - KJV is more strongly worded); John 8:1-42 (Jesus & Samaritan woman)

References are included as in-text links. One is from Wikipedia, which I do not usually source, but the page was exceptional for its citations. There are other sources of information, but given the horrendous details, it can be overwhelming to read.

N.B. My great uncle died when I was quite young, but my family spoke of him and I read his (out-of-print) memoir, My Way to Life, which related his experiences in Buchenwald. My uncle, whom I remember as a gentle and wise man, escaped Germany on the Kindertransport; his widowed mother died in Auschwitz.